The paper Deanonymisation of clients in Bitcoin P2P network (2014) by Biryukov, Khovratovich and Pustogarov (BKP), who describe an attack on Bitcoin Core clients, has started some discussion lately. The main idea of the paper is to first get a set of nodes $E_v$ to which your victim $v$ is directly connected to (“entry nodes”). Second, for each transaction $t$ record the $10$ nodes $P_t$ which first propagate $t$. The authors experimentally show that if $|E_v \cap P_t|$ is bigger than $3$ then there is a pretty high chance that $t$ actually originated from $v$. However, both attack stages basically require a Sybil attack – the attacker has to be connected to a lot of nodes a lot of times. ‘A lot’ means that in their experiments they had 50 connection to each full node (~250) in the test network. As a result, such an attack seems to be powerful, but certainly won’t be undetected.

In this post I show that the first stage of the attack, namely learning the nodes a victim is directly connected to can be done with a single connection to the victim. In addition to BKP’s attack, knowing all outbound peers of a client could significantly increase the success probability of a double spend. Note that all experiments are based on Bitcoin Core 0.9.4, but 0.10.0 shows the same behavior.

TLDR The attacker can reliably guess all of the outbound connections of a victim by making a selection from the known addresses of a victim based on the timestamp of the addresses.

Update A fix has been merged to bitcoind. The timestamp is not updated anymore when receiving a message from a connected peer. Instead, it is only updated when the peer disconnects. The fix is released in bitcoin core 0.10.1.

Learning connections using addr propagation

When a node $n$ connects to another peer $p$ in the network it advertises its address using the “addr” message. The peer will select a number of its own peers at random which are “responsible” for $n$’s address. Then the address is forwarded to responsible peers to spread the knowledge about $n$ in the network. The number of responsible peers is either $1$ or $2$ depending on whether the address is reachable by $p$.

BKP’s attack works by recording the set of peers that first propagated a victim’s address. In order to have good chance to be in the set of responsible peers for the address, the attacker has to hold a significant number of connections to each full node in the network. Note that it is possible to have multiple connections from a single public address to a peer.

The getaddr message

It turns out that an attacker can simply infer the peers of a victim by sending getaddr messages to him.

In bitcoin, the address structures that are send via the addr message do not only contain the IP adress and port but also a timestamp. The timestamp’s role is ensuring that terminated nodes vanish from the networks knowledge and it is regular refreshed by the nodes which have an interaction (more about that later) with the peer at that address. Bitcoin nodes usually record the addresses they hear about and send them in a reply to a getaddr using the addr message.

The following experiments show that an attacker can guess some or all of the direct peers of a victim by sorting the known addresses of the victim based on the timestamp.

A minor obstacle is that a node replies to a single getaddr message only with maximal 2500 addrs selected uniformly at random. In order to get a certain percentage $\tau$ of the known addresses of a node the attacker has to send multiple getaddr messages and record the percentage that is new to her.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Experiments show that if we wait 10 seconds after each getaddr request it takes around $3.5$ minutes to collect $\tau$ percent addresses ($13,500$ in this case).

Experimental results

I set up a victim node $v$, which is just a regular bitcoin node. The attacker $a$ is a node that connects to $v$ via the P2P network and queries the known nodes of $v$. Second, $a$ connects to $v$ via the RPC interface and gets the true peers.

The attacker code (btcP2PStruct) is available on github. Thanks to the btcwire package it is very simple to write this kind of code.

You can find all the data to produce the graphs in the project repository.

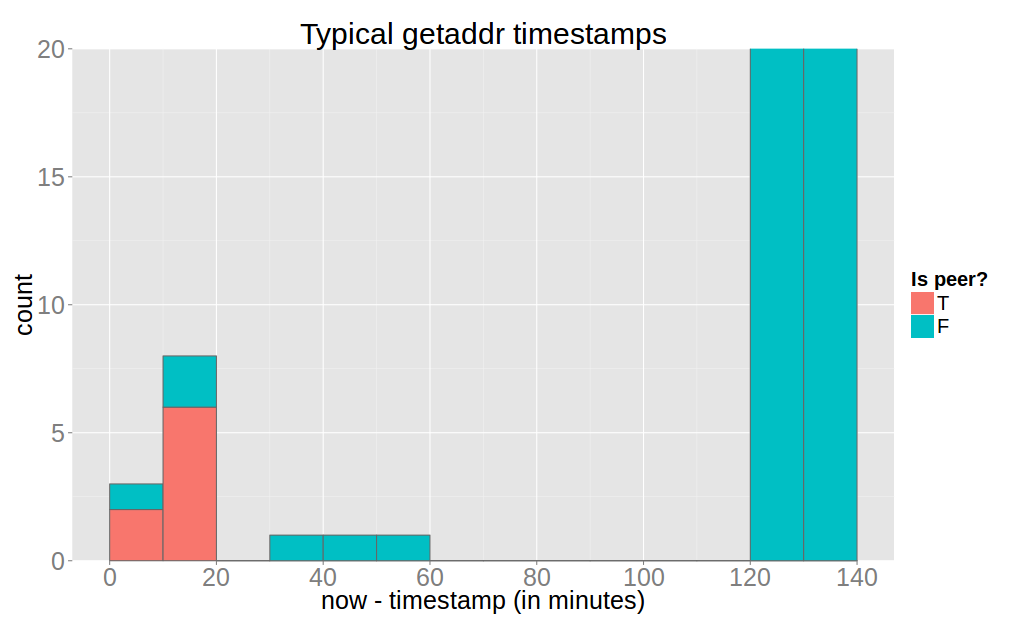

First we consider the case where $v$ does not accept incoming connections (“client” in BKP’s terms). $v$ was running for 2 days and I recorded data for every hour but I will only discuss the last measurement because the data is very similar.

Note that $v$ returned $12,868$ known addresses. Also, a client usually has maximally 8 peers due to the default maximum number of outbound connections. This implies that an attacker can not start start this attack on a client that is not connected to her. Here we see that if the attacker obtains all peers of $v$ (without any false positives in this case).

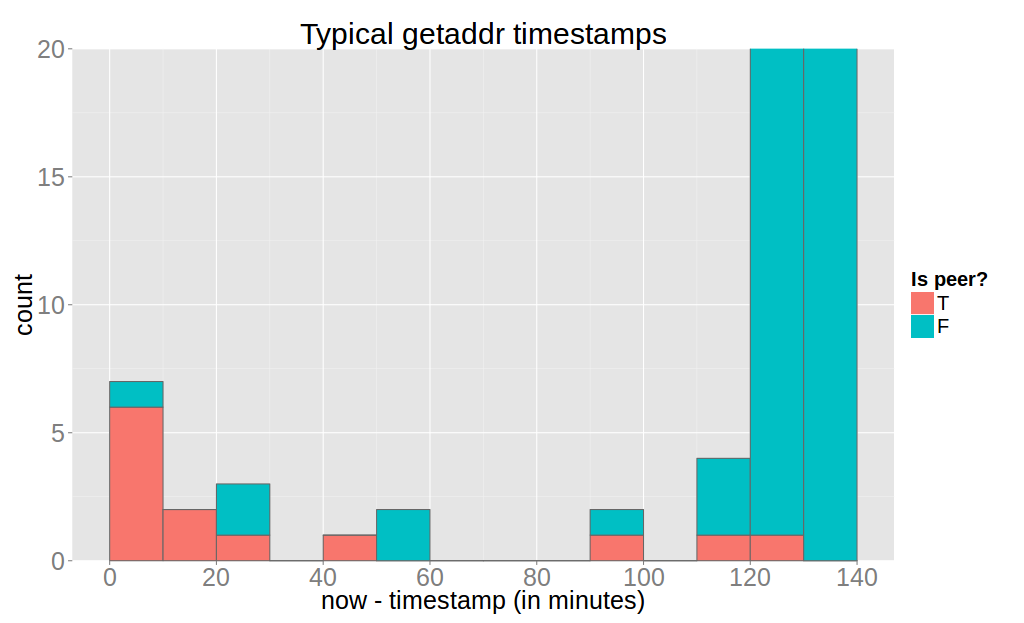

Next, the case for the full node, which I left running for 8 days.

Again it is evident that an attacker can reliably determine all outbound connections of the victim using a threshold of 20 minutes. However, inbound peers can only be detected very poorly.

The reason for finding all outbound peers is is this logic in bitcoin-core which refreshes the timestamp on every message of outbound nodes.

Reducing false positives

BKP mention a neat trick how to determine if two nodes $v_1$ and $v_2$ are connected. First, the attacker connect to $v_1$ and $v_2$ and send addr messages containing bogus addresses to $v_1$. Then, she counts the number of times one of these addresses is received from $v_2$. However, the authors leave open how many messages you need send to be certain about the hypothesis.

As we already know, the address is forwarded only to two responsible nodes so we have to compute the probabilities of our node being responsible. Using the binomial distribution we can compute the likelihood of receiving a certain number of addresses back given that we sent a certain number of addresses.

I’ve done the math using this code and some assumptions regarding the structure (edges are uniformly iid). Also, the attacker has to know or approximate the number of peers of a node, which can be done with a similar method than the one described. Connect two times to the victim, send and note the ratio of returned addr messages. If you can not connect to the node, it will most likely have 8 peers.

This theoretical model shows that that if $v_1$ is a full node and $v_2$ is a client then we need about 2000 messages to determine if they are connected with 95% probability. Similarly, if $v_1$ and $v_2$ are full nodes, the attacker needs to send 20000 messages.

However, in order to remain polite in the network this attack needs start from a candidate set of nodes. Therefore, it could be a useful method to remove the false positives which were obtained with the “getaddr”-fingerprint.

Conclusion

It should be pointed out that even if you know a victim’s entry nodes you can not simply connect to those few and listen for transactions. This is because “trickling” prevents estimating the origin of a transaction without further assumptions or doing BKP’s Sybil attack. However, knowing all outbound peers of a client could significantly increase the success probability of a double spend.

Update The fix removes the update every 20 minutes and updates on disconnect